Doing Social Research

From:

Persell, Caroline Hodges. 1990. “Doing Social

Research.” Pp. 26-36 in Understanding Society:

An Introduction to Sociology. 3rd ed.

New York

,

NY

:

Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc.

Emily M. was like many impoverished children growing up

in a welfare home in the 1960s. The difference for

Emily was that she and a small number of other children were able to attend a

preschool educational program. Careful long-term research by several teams of

social researchers shows that children from such programs are more likely to

graduate from high school and get jobs, or to go for further education, than

similar children who did not attend such a program. Children from preschool

programs are also less likely to get arrested or get pregnant as teenagers

(Deutsch, Jordan, and Deutsch, 1985). The school system operating the program

in

Research studies such as these show how individual lives and society can benefit from particular social programs. Researchers seek to grasp vibrant human issues with scientific procedures. Sociologists do not just sit in their armchairs and spin grand schemes; they go out in the world, observe, talk with people, and systematically analyze existing data to try to understand what is going on and why. This chapter considers some of the ways social researchers do their work. After reading it, you should have a better idea of how social scientists conduct their inquiries; you should be acquainted with a number of important research terms that will reappear in this book; and you should be aware of some of the ethical concerns that confront social researchers. You may also become more aware of your own reasoning processes.

SCIENCE VERSUS EVERYDAY KNOWLEDGE

Most social researchers make every effort to be scientific in the way they conduct their research. To understand better how they proceed, we need to consider how scientific research differs from everyday knowledge. Our everyday knowledge-gathering strategies suffer from a number of weaknesses. We are not always the most careful observers. Considering your friends, for instance, can you say who is right and left-handed? Do you know what color clothing your professor wore the last time you went to class? Unless we work consciously to observe and note behaviors or traits, there is much we can overlook. We also tend to "overgeneralize"–that is, to draw conclusions about many based on only a few cases. Suppose you talk with 3 out of 300 student demonstrators on campus and all 3 say they are protesting the food in the dining room. It is tempting but faulty to infer that all 300 are demonstrating for the same reason.

Left to our own devices, we tend to overlook cases that run counter to our expectations. If you think all football players are politically conservative, you may ignore the ones who are not. Or if you notice some exceptions, you may conclude they are not really football players. Often there is an emotional stake in our beliefs about the world that causes us to resist evidence that challenges those beliefs. This tendency may lead to closing one's mind to new information– an "I've made up my mind, don't confuse me with the facts" approach. Research seeks to overcome these pitfalls of everyday inquiry.

Although some people complain that research is simply an expensive way of finding out what everyone already knew, the results sometimes contradict commonsense expectations. Consider the following statements of the "obvious."

1. Social factors have no effect on suicide.

2. Since there was a steady increase in the number of births in the

3. Men engaging in occasional homosexual acts in the bathroom of a public park belong to a highly visible homosexual subculture.

4. When a number of people observe an emergency, they are more likely to go to the aid of the victim than when only one person is a witness (the "safety in numbers" principle)

5. Stress leads to higher IQ scores in children, since it stimulates them to live by their wits.

6. Religious beliefs are less important to Americans than they are to Europeans. (Everyone knows Europeans are more traditional than Americans.)

All these commonsense statements have been contradicted by careful research studies: (1) Durkheim (1897) presented evidence that social integration strongly affects the rate of suicide among different social groups. (2) In 1970, 19 percent of first-year college students planned a career in elementary or secondary school teaching. By 1985, this figure had plunged to just 6 percent (Astin et al., 1985). The career attitudes of college students were still being shaped by memories of the teacher glut of the 1970s. (3) A study conducted by Laud Humphreys (1970) found that many of the men he observed engaging in homosexual acts in the bathroom of a public park were married, had children, and were model citizens in their communities, very few of them belonged to a homosexual subculture. (4) When witnessing an emergency, a single individual has been found more likely than several people together to help the victim, perhaps because he or she is the only one who can do so (Latane and Darley, 1970). (5) Stress leads to lower IQ scores among children (Brown, 1983). (6) Americans are actually much more likely than Europeans to say that their religious beliefs are "very important" to them. In 1975-1976, 56 percent of Americans felt that religion is very important, compared to 36 percent of Italians and 17 percent of Scandinavians (U.S. Department of Commerce, 1980, p. 523).

The existence of research findings that run counter to what we might expect suggests that we should pause before we say "everyone knows that...." Instead, we should ask: "What evidence do we have for believing that to be true?" Social research is concerned with how evidence is gathered and evaluated.

Science as a Form of Knowing

A central feature of human existence is the desire to know and to understand the world. Knowledge is part of all human cultures, along with strategies for obtaining knowledge and for deciding whether or not something is true. In all cultures the major sources of knowledge are tradition, authority, and observation and reasoning. Cultures differ with respect to how much they emphasize each source. Science flourishes in societies that place relatively greater stress on observation and reasoning. Some societies see the natural and social worlds as caused, patterned, and open to human understanding through observation and logic. Others see the world as mysterious. One way these differences are reflected is in the ways cultures and individuals respond to unknowns. Sometimes they say "We don't know enough yet," as contrasted with "There are many things we will never understand." The former statement reflects a strong faith in science; the latter suggests a more limited view of science.

Social theory and research deal with what is and why it is that way in social life, not with what should be. "Should-be" issues are the concern of philosophy, religion, and ethics, although they invariably color the problems researchers wish to study and the ethical principles they follow in conducting their research. A carefully done research study could add to our understanding, for example, of the social causes and consequences of drug use. How you react to that knowledge depends on your own values. Sometimes personal, religious, or political concerns lead people to deny or ignore unappealing research results. This fact helps explain why research supporting key values or interests tends to be more widely accepted than research that opposes strong values and interests. It also suggests why some research may be utilized by policy makers and other research may not be utilized.

Assumptions Underlying Social Theory and Research

Social theory and research assume there are patterns in social life. This

assumption is sometimes challenged on several grounds. First, there are always

individual exceptions. For instance, whereas whites earn more than blacks in

the

Sociology helps us understand the chances people have of being in certain situations and of behaving in certain ways. Sociologists can make strong statements about the approximate percentage of people who will behave in certain ways, even though they cannot say how particular individuals may act. Similarly, life insurance specialists can say with confidence that nonsmokers in general will live several years longer than smokers; they cannot say that any particular nonsmoker will live longer than any specific smoker. Generalizations and predictions are possible when they deal with large numbers of people, but not when they refer to single individuals. Sociological knowledge permits similar kinds of statements. We can say what percentage of people will behave in a certain way if the social conditions around them do not change drastically, but we cannot predict how a specific individual will act. There is no inconsistency in recognizing a measure of choice available at the individual level while finding patterned behaviors at the collective level. We can know the general tendencies about the sex, race, or class to which we belong and yet still hope that we as individuals will be exceptions to general sociological trends.

The effort to achieve a scientific understanding of human behavior has also been criticized on the grounds that human affairs are extremely complex. Many factors–historical, social, psychological, economic, organizational, societal, and interpersonal–influence human behavior. How can any explanation or prediction take them all into account? No study or theory can include every factor, which is the reason sociologists cannot explain every possibility that may occur. But a study or theory can state that one factor is relatively more important than several others or that something will occur more frequently under one set of conditions than another. Although incomplete and imperfect, this is more accurate than uninformed guesses.

The accuracy of general statements in the social sciences depends on how observations are conducted. The social sciences do not consist simply of one person's opinion pitted against that of someone else. There are rules of evidence and inference that social scientists follow. Some evidence is better than other evidence; some conclusions are more supportable than others. The difference lies in the methodology–that is, in the rules, principles, and practices that guide the collection of evidence and the conclusions drawn from it.

Research differs from everyday inquiry in that researchers try to be conscious of what they are doing, how they are doing it, and what their biases are. Bias refers to the way the personal values and attitudes of scientists may influence their observations or conclusions. Objectivity refers to the efforts researchers make to minimize distortions in observation or interpretation due to personal or social values. Every research report has a section describing what procedures were followed in order to arrive at the results. That section should be explicit enough that another researcher can duplicate the procedure. Researchers also point out the limitations of their work and highlight questions that remain. However, caution is sometimes lost when results are presented in the popular press. Finally, by publishing their work, researchers allow others to question the quality of their procedures, evidence, and conclusions. These practices help to keep inquiry open to new or better evidence.

The Uses of Research

Social research has numerous applications, many of which depend on the ingenuity of the people using it. Leaders in education, business, labor, and government, for example, sometimes use existing or commissioned research to help them decide whether a school should be dosed in a particular neighborhood; whether a university should be decentralized into minicolleges; how teachers should be trained; where a new manufacturing plant should be located; what type of work organization will maximize productivity and minimize absenteeism; what new products should be developed; or how services can be most effectively distributed. Doctors nurses, and other health professionals can gain from research showing ethnic differences in responses to pain and medication or research linking social experience and disease (Brown, 1976). In writing this book, I have used a variety of research tools and strategies. Individuals can use research to investigate schools to attend, careers to pursue, or places to live. Throughout this book I will suggest possible applications of the research and theories we will be considering. As you read the book, you might ask yourself– what are the implications of these ideas for my life, my family, my community, and my career?

The general importance of social research is highlighted in a report by the National Academy of Sciences (Adams et al., 1984) that credits social science researchers with inventing information-generating technologies. Of these, the most important is the sample survey, which includes household sampling techniques, personal interviews, and questionnaires and data collection in experimental settings. "The sample survey has become for some social scientists what the telescope is to astronomers, the accelerator to physicists, and the microscope to biologists–the principal instrument of data collection for basic research purposes."

Social scientists, governments, and many private organizations now use the sample survey as their primary means of collecting information. "The statistical systems of most industrialized nations, which provide information on health, housing, education, welfare, commerce, industry, etc., are constructed largely on the methodology of sample surveys" (Adams et al., 1984, p. 65). The data and research findings generated by these techniques are useful in many walks of life. "Our notions about ourselves and each other–about racial differences, for example, or the nature of childhood–have been radically transformed by the dissemination of social and behavioral research findings," and "it is fair to say that as a result of such research Americans today have a different view of human behavior and social institutions than their parents did a generation ago" (Adams et al., 1984, p. 89).

Race and ethnicity is probably the area in which behavioral and social science research has caused the greatest change in perception. For example, there has been a dramatic shift through the twentieth century in the Encyclopaedia Britannica's description of the mental abilities of blacks. In 1911 the encyclopedia stated: "Mentally, the negro is inferior to the white." By 1929, based on research obtained in the intervening years, it read: "There seem to be no marked differences in innate intellectual power." By 1974 the encyclopedia attributed differences in scores on intelligence tests to environmental influences that "reflect persistent social and economic discrimination" (Adams et al., p. 86).

The

DEFINITIONS AND PROCEDURES

Part of encountering any new field involves learning the names of some of the "tools of the trade," so that you know what people are talking about. If you are learning to work with wood, for example, it helps to know the difference between a claw hammer and a ball-peen hammer, so that you will use the right one. To understand a piece of social research, you need to know the unit of analysis in a study; what sampling procedures were used; the difference between a descriptive and an explanatory study; what a hypothesis is; and how concepts, variables, operational measures, and relationships between variables are defined. (Additional tools of the trade are presented in the boxes throughout this chapter.)

A second step in exploring a new area involves learning something about the procedures people use to do their work. Certain procedures used in research are very powerful; they enhance our potency in everyday life as well as in social research. At the top of this list are rules for believing that one factor may have caused another one and the steps in doing research.

Some Research Terms

Units of Analysis

One of the first things to know about research is the unit of analysis–that is, who or what is being studied. Social researchers often look at individuals–at their attitudes or behaviors. Sometimes the unit of analysis that interests us is something larger, like a social group or an organization. For example, studies have found that some hospitals have lower rates of infectious hepatitis among their patients than others (Titmuss, 1971, p. 146). Several summary measures of data are discussed in the box on mean, median, and mode. Although the rates were compiled by adding up the total number of individuals who caught the disease and dividing by the total number of people in the hospital, the unit of analysis was the hospital and the research question was "Why should some hospitals have higher rates than others?" The explanation lay in the sources of blood used by different hospitals rather than in the patients' medical histories. Teaching hospitals received blood for transfusions from volunteer donors, whereas some other hospitals were more likely to purchase blood from private blood banks that paid individuals to give blood. People selling their blood were more likely to have hepatitis than were people giving blood voluntarily. If the unit of analysis had been individuals who contracted hepatitis in the hospital, this research might never have been solved. Looking at the hospitals as the unit of analysis raised new questions and supplied answers.

Units of analysis can also refer to families, ethnic groups, nation-states, or societies, when appropriate. Social artifacts such as books, TV shows, sculptures, songs, scientific inventions, and jokes could all be units of analysis for social research.

Descriptive and Explanatory Studies

There are two major types of research studies: descriptive and explanatory.

In a descriptive study the goal is to describe something, whether it is

the behavior and values of a religious cult, the culture of an old-age

community, or the nature of a national population. Such studies help to outline

the social world. Explanatory studies seek to explain why or how things

happen the way they do in the social world. An explanatory study might seek to

explain why crime rates are much lower in

Hypotheses

A hypothesis is a tentative statement– based on theory, prior research, or general observation–asserting a relationship between one factor and something else. A descriptive hypothesis is a tentative statement about the nature or frequency of a particular group or behavior.

For instance, the statement "People find jobs through various means, including answering advertisements and being referred by friends" is a descriptive hypothesis that can be verified by research. An explanatory hypothesis tries to link one variable (such as a behavior) with another variable, as in the statement "How someone finds a job is related to income in that job."

Researchers try to design studies to test whether or not their hypotheses are true and to rule out rival hypotheses (that is, explanations that compete with the original hypothesis). They reason the way a detective does in trying to figure out who the murderer is. The data uncovered in a study may support the original hypothesis, refute it, support a rival hypothesis, or suggest conditions under which the hypothesis is supported. This method of reasoning goes beyond the testing of academic social science hypotheses. It is widely used by market researchers to test ideas for designing and selling new products or services, by political candidates seeking to understand public sentiments, and by policy makers developing new social programs.

Figure 2.1 The Continuous Cycle of Science.

Science develops as theories generate hypotheses that guide specific observations. A number of specific observations begin to form sets of general research findings, which may shape future theories.

Source: Adapted from Wallace, 1971, p 18.

One source of hypotheses for a research study may be social theory, which can be defined as a system of orienting ideas, concepts, and their relationships that provide a way of organizing the observable world. The interplay between theory and research is shown in Figure 2.1. In this model, theories suggest hypotheses, which lead to observations, which produce research findings, which, in turn, may modify theories, generate new hypotheses, and so on. Scientists may step into this circle at any point and work to advance knowledge

Deduction refers to reasoning from the general to the specific. A general theoretical statement is confirmed or refuted by testing specific hypotheses deduced from it. Induction refers to reasoning from the particular to the general. The truth of a theoretical statement becomes increasingly probable as more confirming evidence is found. There is always the possibility of a disconfirming case, however.

Concepts and Variables

Suppose you want to investigate the question of whether job-finding strategy

is related to income. One of the first steps in any research study is to define

the concepts–in this case jobfinding strategies and

income. A concept is a formal definition of what is being studied.

Researchers must define what their major concepts include and do not include, what they are like and unlike. In research,

concepts are refined further into variables. A variable is any quantity

that varies from one time to another or one case to another. Variation can be

seen in different categories or in different degrees of magnitude. For example,

in the

A proposition is a statement about how variables are related to each other. It is similar to a hypothesis, which is a tentative statement about how variables might be related to each other. Usually a hypothesis is stated so that it may be tested empirically (that is, through systematic research and analysis) and verified or rejected.

Operationalizing Variables

Variables are said to be operationalizedwhen we define the procedures used to measure them. One procedure for measuring job-finding strategies would be to follow people around as they looked for a job. But most people do not want researchers hovering around while they look for a job, and such a procedure would take a long time. For these reasons, researchers often use interviews to find out what people do. So we say that the variable, job-seeking strategy, is operationalized in terms of one or more questions in an interview.

Mark Granovetter (1974), who did an operationalized study of professional, technical, and managerial workers, asked the following question to learn how people found out about the most recent job they had obtained:

How exactly did you find out about the new job listed [above]?

a. I saw an advertisement in a newspaper (or magazine, or trade or technical journal).

b. I found out through an employment agency (or personnel consultants, "headhunters", etc.).

c. I asked a friend, who told me about the job.

d. A friend who knew I was looking for something new contacted me.

e. A friend who didn't know whether I wanted a new job contacted me.

f. Someone I didn't know contacted me and said I had been recommended for the job.

g. I applied directly to the company.

h. I became self-employed.

i. Other (please explain):

He also asked their income in their present job.

Relationships Between Variables

Frequently hypotheses suggest that a change in one variable causes a change in another variable. If one variable is thought to cause another one, we call the first variable the independent variable and the second variable the dependent variable, because it is believed to depend on the independent one. Put differently, the independent variable is the hypothesized cause and the dependent variable is the hypothesized effect. In this example, job-finding method is the independent variable and income is the dependent variable.

In Table 2.1, Granovetter's respondents have been grouped according to the method they used to find their jobs. Fifty people used "formal means" such as advertisements, public or private employment agencies, or the placement offices of their colleges. Using formal methods meant that job seekers used the services of an impersonal "go-between" to get in touch with potential employers. The method of"personal contacts" was used by more respondents (154) than any other method. This meant that respondents knew someone personally who told them about their new job or recommended them to an employer, who then contacted them. Respondents had become acquainted with their "personal contacts" in some setting unrelated to the search for job information. "Direct application" was used by 52 respondents. This method meant that respondents went to or wrote directly to an employer, without using any go-betweens and without hearing about a specific opening there from a personal contact. Nineteen people used some other method (Granovetter, 1974, p. 11).

Table 2.1 shows the strong association of income level with job-finding method. Nearly half (45 percent) of those using personal contacts report incomes of $15,000 or more (these interviews were done in 1969, when that represented a much higher income). Among those who used formal means, only one-third reported such high incomes; and among those who applied directly, less than one-fifth reported incomes of $15,000 or more. Another way to summarize these results is to say that there is a correlation between job-finding method and income level. A correlation is an observed association between a change in the value of one variable and a change in the value of another variable.

Inferring Causality

Although we can say that the two variables are correlated, we cannot say at this point that one caused the other. Correlation is only the first piece of evidence needed to decide that one factor caused the other one. We also need to know that the independent variable occurred before the dependent variable (a time order that is clear in this example), and that no other factors might have caused the observed result. Many other factors–such as age, religious background, or occupational specialty of job seekers–might affect income. Without evidence ruling out alternative explanations for the observed relationship between job-finding method and income level, we cannot infer that the way people found their jobs caused them to earn higher incomes. (Granovetter was not interested in pinpointing the causes of income variation but rather in understanding the dynamics underlying the way people find different kinds of jobs, so he did not pursue an analysis of causes.) In general, social researchers try to rule out alternative explanations by controlling for other factors that might be affecting the relationship. In this example, for instance, Granovetter found that religious background had no particular impact on the chances of using a given method, but that age was related–job seekers over 34 were more likely to use personal contacts. You should get from this example a sense of the kind of reasoning social researchers follow when they are testing explanatory hypotheses.

No matter how strong a correlation is, it is important to remember that it does not indicate causality unless time order and the elimination of alternative explanations are also present. We can sharpen our everyday thinking and our critical appraisal of causal claims made by others by asking whether all three of these criteria are being met.

Suppose, for example, you have a job, but you have not received a raise in three years. Can you infer that your boss is not pleased with your work? Applying the research orientation to everyday life suggests a number of questions: Do you have any direct indicators of how your boss feels about your work? Did anyone else where you work get a raise? What else might be affecting whether you get a raise (for example, is the boss making money)? What might the boss expect you to do if you do not get a raise? Can the boss replace you with someone as good for the same or less money? What kind of bargaining power do you and other employees have? There are many rival explanations for why you did not get a raise, only one of which consists of the boss's appraisal of your work. Thinking like a researcher can help you assess the evidence for inferring that one factor caused another.

The strongest way to rule out all rival explanations is to conduct a tightly controlled experiment where subjects are randomly assigned to two groups, only one of which is exposed to the independent variable while the other is not. Happily, no experimenter has the power to assign us randomly to groups and then tell us how we must or must not find a job so that the effect on our income can be studied. Many areas of sociological research share these ethical and practical constraints. In such situations we can only try to approximate the logic of experimental designs by controlling for as many rival explanations as possible.

Although not all research studies follow the same pattern, it is possible to spell out the steps that occur frequently in the research process.

Defining the Problem

Defining the problem involves selecting a general topic for research, identifying a research question to be answered, and defining the concepts of interest. Individuals have personal research questions, and social researchers have more general ones. You may wonder, for example, how you will get your first job. On a larger scale, sociologists might ask how people in general find jobs, as Granovetter did (1974).

Reviewing the Literature

The next step is to review the existing literature to determine what is already known about the problem. Prior work may offer general descriptions, raise some key questions, discuss the strengths and limitations of measures that have already been tried, and suggest profitable lines of further research. More and more libraries offer computerized literature searches that speed up the review process.

Devising One or More Hypotheses

Ideally, in their effort to build knowledge, researchers develop several competing hypotheses. Durkheim (1897) did this in his classic study entitled Suicide. He considered the possibility that suicide rates varied as a result of heredity, climate, or social factors. He found social factors, such as the presence or absence of cohesion within a social group, to be the most important determinant of suicide.

Designing the Research

Researchers then decide on a design for the study that will allow them to eliminate one or more of the hypotheses. Research design is the specific plan for selecting the unit of analysis; determining how the key variables will be measured; selecting a sample of cases; assessing sources of information; and obtaining data to test correlation, establish time order, and rule out rival hypotheses.

Collecting the Data

Sociologists gather information in a variety of ways, depending on what they want to investigate and what is available. They may use field observations, interviews, written questionnaires, existing statistics, historical documents, content analysis, or artifactual data. Each of these methods will be discussed briefly in the next section.

Analyzing the Data

Once the data are collected, they must be classified and the proposed relationships analyzed. Is a change in the independent variable indeed related to a change in the dependent variable? Can time order be established? Are alternative explanations ruled out?

Drawing Conclusions

Drawing conclusions involves trying to answer such questions as these: Which of the competing hypotheses are best supported by the evidence? Which are not? What limitations in the study should be considered in evaluating the results? What lines of further research does the study suggest? Conclusions rest heavily on the way research is designed and data are gathered.

DESIGNING STUDIES AND GATHERING DATA

Social researchers study and try to understand the social world. Either they seek to describe some feature of social life or they try to analyze and explain interrelationships among social factors. Various types of data are available for both goals, and those data may be collected in different ways.

Experiments

Does early childhood education for children living in poverty help them to succeed in school and beyond? In a social experiment, the researcher tries to see whether a change in the independent variable (in this case, exposure to a preschool program) is related to a change in the

dependent variable (school success or failure,

criminal arrests, teen pregnancies, unemployment,

and the need for welfare), while other

conditions are held constant (family and neighborhood).

In an experimental design, the effect of the

independent variable is assessed by comparing

two groups of people. One group, the experimental

group, is exposed to the hypothesized

independent variable (the preschool program),

while another group, the control group, is not.

To rule out other explanations, the experimental

and control groups must be identical in every

respect except their exposure to the treatment.

In the Perry preschool study there was an

experimental group of 58 and a control group

of 65. They were selected for the study at age 3

or 4 on the basis of parents' low educational and

occupational status, family size, and children's

low IQ (intelligence test) scores. Pairs of children

matched on IQ, family socioeconomic status,

and gender were split between the two

groups. The experimental group attended a preschool

program for two years. Studies of the

Perry Preschool Program in Michigan and five

other preschool programs show significant differences

between children in the experimental

and control groups in terms of their higher intellectual

performance as they began elementary

school, their lesser need to repeat a grade or to

receive special education, and their lower rates

of dropping out of high school. In the Perry

preschool study, the two groups were also compared

in their early adult lives. Nineteen-year olds

who had attended the program were better

off in a variety of ways than the control group.

The program seems to have increased the percentage

of participants who were literate (from

38 to 61 percent), enrolled in postsecondary education

(from 21 to 38 percent), and employed

(from 32 to 50 percent). Moreover, the program

seems to have reduced the percentage of participants

who were classified as mentally retarded

during their school years (from 35 to 15 percent),

school dropouts (from 51 to 33 percent),

pregnant as teenagers (from 67 to 48 percent),

on welfare (from 32 to 18 percent), or arrested

(from 51 to 31 percent) (Schweinhart and Weikart,

1987, pp. 91-93).

Experiments are strong methods for meeting

the three criteria of time order, correlation, and

the elimination of rival hypotheses needed for

inferring causality. They are limited by the practical

and ethical restraints that exclude the study

of private or dangerous behavior. Another

method--interviews--can help researchers to

obtain information about private, personal, or

taboo attitudes and behaviors.

Interviews and Surveys

What kind of gender-role behavior occurs between

long-term partners in a relationship? Are

there differences in the gender roles people assume

when couples are straight (heterosexual)

and gay (composed of two homosexual men or

lesbian women)? These are some of the research

questions posed by Philip Blumstein and Pepper

Schwartz (1983), two sociologists at the University

of Washington. To investigate these and

related issues, they conducted interviews with

more than six hundred people living in long-term

relationships, and they mailed a written

questionnaire to more than ten thousand people

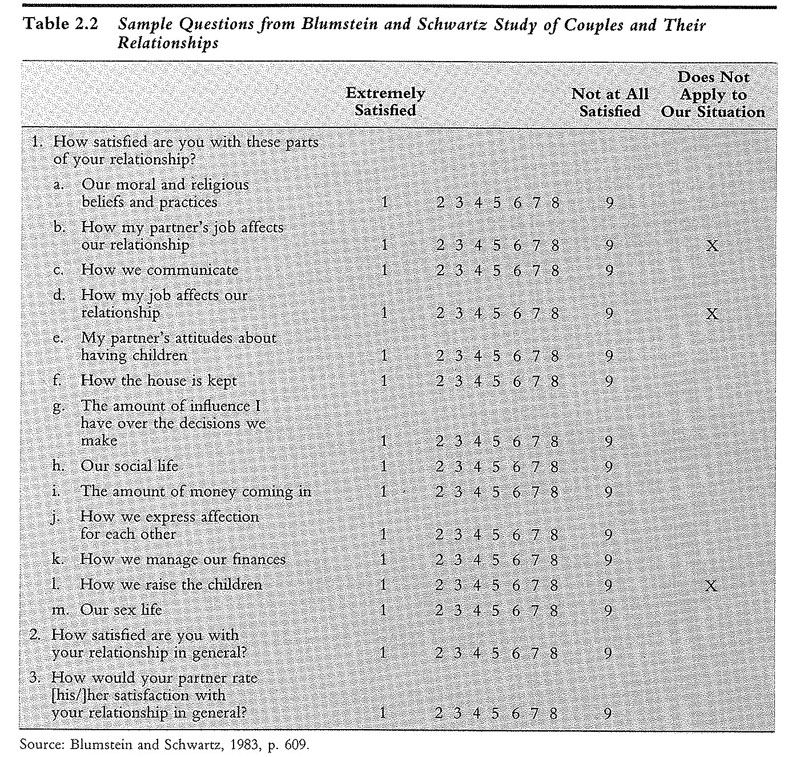

who agreed to participate in the study. (See Table

2.2 for a sample of some of the questions

that were asked in this study.) Although carefully

protecting the identities of the individuals

involved, the researchers collected background

information on the respondents' educations, ccupations,

incomes, and ethnicity, as well as

considerable information about their relationships

with their partners.

The use of interviews and questionnaires enabled

them to ask everyone the same questions,

so that comparisons could be made between

long-term and short-term couples; between gay,

lesbian, and straight couples; between couples

with children and those without; and so forth.

Practical and ethical considerations would have

made it impossible to gather such data by observation,

and other methods of data collection

would have been equally inappropriate. Surveys

are useful for describing the characteristics of

large numbers of people in an efficient way. In this case, if only a few individuals had been

studied, we might think that the results were

unique to them and did not occur in the larger

population. Surveys of carefully selected samples

permit the accurate determination of rates

of behavior or the frequency with which certain

attitudes are held.

Sampling Procedures

The special sampling procedures researchers have developed are among the most powerful tools in their kit. Properly done, sampling permits conclusions about entire populations (of individuals, groups, organizations, or other aggregates) by studying only a few of them. The key lies in how those few are selected. A population is the total number of cases with a particular characteristic. Suppose you were interested in the sexual attitudes of American college students. Do you think you could walk out the door (wherever you are) and select the first ten warm bodies you encountered, interview them, and draw accurate conclusions about the attitudes of all college students? Such a technique is likely to be very unrepresentative. To overcome this problem, researchers use random sampling.

There are many types of scientific samples. In a random sample, every element (person, group, organization, or whatever) of the population must have an equal and known chance of being selected for inclusion in the sample. There is solid technical knowledge available about sampling, but we cannot cover it all in an introductory sociology text. If you pursue a career in social research, you will learn more about the strengths of sampling techniques. Properly done, sampling allows researchers to judge the likelihood that their results could have occurred by chance.

Surveys work only when respondents are able

and willing to report what they know, do, or

feel. One of the limitations of survey research

is the need to standardize the wording of questions

and, in precoded versions, the allowable

responses. This may lead to the problem of people

not understanding what a standardized question

means, or not finding the answer they want

to give. Such limitations can be overcome by

using open-ended or depth interviews before

developing precoded response categories. Field

research can also be used prior to designing a

survey so as to get a better understanding of

what is important to people, what meanings

different words have for them, and how social

processes unfold. Without depth interviews

prior to questionnaire design, it is often impossible

to know what questions to ask or how to

ask them.

Observational Research

Field research involves going where people are.

It includes observation and sometimes participant

observation, in which the researcher

makes observations while taking part in the activities

of the social group being studied. In her

study of how policewomen were accepted by

others in the force, Martin (1980) worked as an

auxiliary policewoman and actually went out on

patrol with other officers. She found that policemen

developed a closed occupational brotherhood

and expressed serious opposition to the

entry of policewomen, although some younger

and more critical officers were willing to accept

women as colleagues. A social researcher can do

fieldwork by being a complete participant, only

an observer, or anything in between.

The ability to observe in field research can be

enhanced by recording devices, just as the ability

to listen in interviews can be aided by a tape

recorder. Film, still photography, and videotape

can add to the ability to record and later note

(and code) specific behaviors. Videotape or film

is particularly useful for studying interactions.

For example, using film that could be studied

frame-by-frame, Stern (1977) and others were

able to observe in caregiver-child interactions

whether the caregiver or the child moved first

toward the other. They expected that caregivers would initiate all contacts with babies but found

that infants often initiated movement toward the

caregiver, who then became involved. To the

unaided eye, the movement occurred so fast that

it was impossible to unravel without the help of

a tool to slow down the process.

Still photograpby provides a check on visual

memory. It allows researchers to record cultural

and social events precisely. These records can

then be studied by people who were not present

when they were made. Cameras share the same

limitations that affect all human observation.

They are subject to bias or personal projection in

terms of what we select to "see" or "film,"

how we frame a picture, and what we combine

within a picture. This is particularly true of digital photography.

Another potential instance of bias arises when we present interviews on film or videotape. Do researchers select sympatbetic and likable people to express certain views, or are the spokespersons unattractice or unsympathetic? Obviously, in such techniques, social research borders on journalism and the mass media. Similar questions can be raised in both: What is being included and what excluded? How representative are the people selected? How were they sampled?

Other Sources of Data

Existing Data and Government Documents

Government documents are a major source of

social statistics. The United States and many

other governments spend millions of dollars

each year gathering information from residents

and private and state sources. World statistics

are available through the United Nations Demographic

Yearbook, which presents births,

deaths, and other vital statistics for individual

nations of the world.

Governments vary in how carefully they collect

social statistics. Crime waves have risen and

fallen merely because the crime data were recorded

by different administrators. In developing

nations, where many babies are born at

home, birth records may be very incomplete.

Wealthier nations can afford to spend more

money to gather systematic data. The General

Social Survey (GSS), for example, done by the

National Opinion Research Center (NORC) with U.S. National Science Foundation support,

is an annual or biannual social survey of about 1500

Americans that was begun in 1972. It taps beliefs

and opinions about public affairs, perceptions of

well-being, and reports of social behavior. Such

surveys over time permit the analysis of social trends and changes.

The data from surveys such as these are

available on the World Wide Web to persons who want to analyze them

further. NORC

also publishes the "codebooks" on line, which list

the questions asked, the answers given by people

in the sample, and more information on the

sample design.

Comparative Historical Methods

In order to make causal inferences, one must

study events over time and compare cases that

differ in certain key respects but are similar in

other important ways. For some problems this

is possible only by using historical materials. In

her study of revolutions, Theda Skocpol (1979)

utilized comparative historical analysis. This

method is appropriate for developing explanations

of large-scale historical phenomena of

which only a few major cases exist (such as

revolutions within entire nation-states). Skocpol's

problem was to identify and validate the

causes of social revolutions. Her strategy was to

find a few cases that shared certain basic features.

France, Russia, and China were similar in

their old regimes, their revolutionary processes,

and the revolutionary outcomes. All three revolutions

occurred in wealthy and politically ambitious

agricultural states, none of which had

ever been the colony of another state. All three

suddenly faced a military competitor that was

more developed economically than itself. External

problems combined with widespread peasant

rebellions and competing political leaders. The result in each case was a centralized and

bureaucratic nation-state with potential for considerable

international power. The analysis of

these three cases is an example of the method of

agreement, where similar causal chains appear

in several situations.

Unobtrusive Measures: Physical Traces and

Artifacts

Some of the methods mentioned so far are

limited by the fact that when people know they

are being studied, they may try to influence

what is learned about them. One solution is to

look for nonreactive measures--that is, indicators

that do not change because they are being

studied. For example, one could assess the

amount of drinking that occurs on a "dry" college

campus by counting the number of beer,

wine, and liquor bottles in the trash rather than

by asking people about their drinking behavior

(Webb et aI., 1966).

Content Analysis

How can we analyze the mass media? The

method, content analysis, is used to describe

and analyze in an objective and systematic way

the content of literature, speeches, or media. It

helps to identify cultural themes or trends.

Alone it cannot tell us whether people think or

behave differently as a result of reading certain

stories, but it can measure the ideas that are in

circulation.

For example, the reactions of working-class

women to the experience of miscarriage and

infant death were analyzed by studying the content

of articles on the subject that appeared in

the magazine True Story from 1920 to 1985.

Some women blamed themselves for the creation

of their own tragedies, and mothers were

taught to doubt themselves and rely on male

authorities. Other women came to accept death

as part of life and learned to enjoy other relationships

more fully as well as to validate other

women's experiences by their writing (Simonds,

1988).

References

Adams, Robert McCormick, et al. 1984. Behavioral and Social Science Research: A

Astin, Alexander W., Kenneth C. Green, William S. Korn, and Marilynn Schalit. 1985. The

American Freshman: National Norms for Fall 1985.

Blumstein, Philip and Pepper Schwartz. 1983. American Couples: Money/Work/Sex. New York: Morrow.

Brown, Bernard. 1983. “Stress in Children and Families.”

Paper presented at annual meeting of

the American Association for the Advancement of Science,

Brown, G. 1976. “The Social Causes of

Disease.” In An Introduction to

Medial

Deutsch, Martin, Theresa J. Jordan, and

Cynthia P. Deutsch. 1985. “Long-Term Effects of Early

Intervention: Summary of Selected Findings.” Xeroxed report,

Durkheim, Emile. 1897/1951. Suicide.

Fiske, Edward B. 1984. “Earlier Schooling Is Pressed.” New York Times (December 17): A1, B15.

Granovetter, Mark S. 1974. Getting a Job: A Study

of Contacts and Careers.

Humphreys, Laud. 1970.

Tearoom Trade: Impersonal Sex in Public Places.

Latane, Bibb and John M. Darley. 1970. The Unresponsive Bystander: Why Doesn’t He

Martin, Susan E. 1980. Breaking and Entering: Policewomen on Patrol. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Simonds, Wendy. 1988. "Confessions of Loss: Maternal Grief in 'True Story.'" Gender & Society 2:149-71.

Skocpol, Theda. 1979. States and Social Revolutions. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Stern, Daniel. 1977. The First Relationship: Infant and Mother. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Titmuss, Richard M. 1971. The Gift Relationship.

U.S.

Wallace, Walter L. 1971. The Logic of Science in Sociology.