Hernando was born and raised in Heredia, a small agricultural community in central Mexico with an established history of emigration to the United States. He left school at the age of eight to help his father farm their land. Seeking adventure he later decided to migrate to the United States, to Georgia where he had friends. There, Hernando found an apprentice position with a master carpenter.

Through observation and informal on-the-job learning, Hernando became a skilled craftsman. After four years of working under the supervision of his mentor, Hernando had saved enough money to return home to Mexico and launch his own woodworking business.

Today he is the proud owner of a woodworking enterprise that provides U.S.-style cabinetry and furniture to the growing return migrant population in his community. Like many other return migrants who launch entrepreneurial activities, Hernando mobilized new technical and social skills acquired in the U.S. labor market to train his employees and carve a new niche in the local Mexican economy, one driven by return migrants who desire U.S. building styles.

Hernando is one of hundreds of thousands of migrants who have returned home to Mexico from the United States since 2010. In a recent study, we investigate the implications of return migration for economic growth and development in Mexico.

While numerous studies have documented a high rate of business formation among return migrants relative to non-migrants, most scholars treat migration as a source of financial capital to invest in businesses upon return home, rather than a pathway to skill learning and transfer. In a recently published study, we explore the relationship between skill formation in the United States and business formation upon return to Mexico.

We draw on findings from a survey of 200 migrants and 200 non-migrants in León, a large industrial city in west central Mexico. León was selected as the research site because its diverse industrial base captures a range of total human capital, which allowed us to examine opportunities for skill transfers, economic mobility, and business formation.

As well as completing a demographic survey, each of our respondents relayed to a personal narrative of lifelong work experience and skill development and transfers across the Mexico-U.S. migratory circuit. Recognizing the importance of workplace learning and industrial context of skill transfers, the research team also conducted more than a dozen worksite observations of return migrant businesses, which ranged from small and medium sized sundry stores, auto repair shops, cyber cafes and restaurants, and shoe and leather workshops and factories.

Skill learning and business formation

While prior studies have emphasized the role of financial remittances, our results highlighted the centrality of skill learning and transfer to business formation. For Mexican workers like Hernando, with low levels of traditional human capital as measured through education and formal credentials, skills learned informally on the job in the United States create opportunities for innovation in established industries and enable migrants to create new economic niches. Our research focused on three types of skills acquired in the United States and transferred to Mexico: English language, social, and technical.

We found that the application of skills learned in the United States to work in Mexico is associated with a two-fold increase in the odds of starting a new business with at least one employee (we did not consider own-account work as it includes primarily marginal self-employment). This association was not attenuated by the inclusion of traditional human capital variables (education and work experience), indicating that skills learned in the United States provide a mobility pathway for individuals with low levels of traditional human capital.

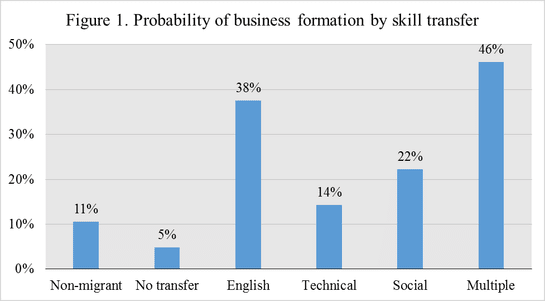

We also investigated variations in the relationship between skill transfer and business formation by skill type. Figure 1 presents the probability of starting a business among non-migrants and among return migrants according to the type of skill transfer. Only 5% of return migrants who did not acquire new skills started businesses upon return, indicating that skill formation is a critical pathway to mobility among Mexican migrants. By contrast, all three types of skills were associated with a greater probability of business formation. Nearly 50% of migrants who learned and transferred multiple types of skills started businesses upon return, 4.5 times the rate of business formation among non-migrants.

Lifelong human capital formation

Among migrant workers with little schooling, on-the-job learning and skill formation is a lifelong process that begins in the migrants’ homes and communities, and then continues in their workplaces before, during, and after migration. Mexican migrants who transfer skills learned on-the-job in Mexico to their work in the United States are in turn more likely to acquire new skills in their U.S. jobs and transfer those skills back to Mexico.

For workers with little schooling, skills learned on-the-job in Mexico and the United States create opportunities for occupational advancement – moving to more highly skilled positions that offer new opportunities for learning. Among migrants who enter low-skilled gateway jobs in the United States, advanced technical skills often enabled them to advance to more skilled positions, with higher wages, and greater opportunities to learn new skills, which in turn increased their rate of business formation upon return to Mexico.

Skill learning, lifelong human capital, and social mobility

On-the-job skill formation represents an important, and under-studied mobility pathway among Mexican migrants with little schooling. Measures such as migration duration and number of U.S.-jobs, which are the primary markers of skill learning used by most migration researchers, provide poor indicators of skill formation. Studies of mobility among migrants and other populations with low levels of traditional human capital, should incorporate direct assessments of skill formation to capture the importance of on-the-job learning and lifelong human capital formation to social and economic mobility.

Jacqueline Maria Hagan is Robert G. Parr Distinguished Term Professor of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Joshua Wassink is a PhD candidate in the department of sociology at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This article is based on their paper ‘New Skills, New Jobs: Return Migration, Skill Transfers, and Business Formation in Mexico’ in Social Problems.

This article originally appeared in the ASA Section Work in Progress blog, December 14, 2016. Work in Progress – or WIP – is cosponsored by four Sections of the ASA:

- Organizations, Occupations and Work

- Economic Sociology

- Labor and Labor Movements

- Inequality, Poverty and Mobility