The University of Nebraska-Lincoln (UNL) is an R1 (doctoral granting and high research activity) institution with decades of experience with community-engaged research (CER). The UNL Sociology Department has long emphasized research methods, particularly survey methodology and social network analyses, in academic and practice settings. The department offers many opportunities to conduct CER, as well as general applied sociology, and encourages faculty to publish with students out of those opportunities. In part through insights gained through ASA efforts (e.g., leadership development about careers in practice settings), and in part learning from graduate students who perceived discouragement from considering jobs in applied settings, as department chair coauthor McQuillan encouraged efforts to promote paths to possible careers in multiple kinds of settings (e.g. as professors, in government agencies, nonprofit, and for-profit settings).

Our impression is that many faculty in R1 universities are most comfortable mentoring students to careers in academia. Lack of familiarity with applied careers can lead to unfortunate concerns, such as faculty telling students they are “throwing away a career.” However, graduates from the UNL Sociology Department make vital contributions to societal wellbeing through studying and effectively communicating results in settings such as a global religious organization, global hiring consulting firms, government agencies, for-profit companies, and health research. There can also be worries about department reputational prestige if students are not placed in academic positions. UNL department members in 1998 explored the question of what matters most for reputational prestige and found that past prestige was so much more important than student placement and current faculty publishing that many of us decided to focus on supporting our students in their chosen career path rather than trying to mold students to pursue positions that we thought would elevate the department reputation.

The UNL Sociology Department has several structured opportunities to engage in applied research that help our graduates to be competitive in academic and practice settings. For example, the Bureau of Sociological Research, (BOSR), an academic survey organization, provides practical experience to graduate students. Some students use those experiences to design studies and collect data as faculty, and others go on to work in government, private industry, and nonprofit organizations. We argue that CER is an important and valuable practice that can enrich sociology students’ experiences, forge valuable connections in the community, and provide useful opportunities for department members and communities. In this article we will provide examples of different types of CER.

Community-Engaged Research at UNL

When we conduct CER, we share the power to define the goals of the research with stakeholders, community members, and study participants. In different disciplines, CER may be referred to as community-based participatory research or participatory action research. Even with different names, the key elements of CER are applied, action-oriented work; long-term, authentic partnerships; and equitable solutions to social problems.

Because the National Science Foundation required social science expertise on ADVANCE institutional transformation grants, we (McQuillan and Hill) designed studies that simultaneously treated STEM departments as community-based partners (e.g., learning from department chairs the importance of dual-career hiring), evaluated interventions, and tested sociological theories. (For more examples of this kind of research, see the “Gender Transformations of Higher Education Institutions” special issue of Gender & Society. Login required.)

We also collaborated on an NSF Engineering Research Center (ERC) proposal to create a new, controversial manufacturing industry—cellular agriculture. ERC proposals require convergent science; thus, we embedded sociology throughout the proposal, not only in the research and evaluation sections. For this project we did not think the engineers and food-scientists should be considered our community partners. Guided by CER and a framework from the European Union on responsible research and innovation, we proposed working with stakeholder groups (e.g. consumers, food producers, regulators, and policy makers) to meet food security needs and guide the new industry to create accessible food and desirable jobs.

When sociologists and community partners discover common interests through building relationships, they can use CER to create “win-win” solutions. For example, our UNL-led sociological research team wanted to discover if youth responses to comics versus essays on similar science topics depend upon how much youth identify as “science kinds of people.” A local area school district was also interested in learning about the educational utility of science comics. Our shared goal led to a field experiment in which ninth-grade students were randomly assigned to read essays or comic books on the same scientific topic. Afterward, youth knowledge did not differ in the two conditions, yet youth with low science identities were as interested as those with high science identities in engaging with the scientific material when it was in the form of a comic, but not as interested when it was in the form of an essay. These combined efforts served the goals of the district teachers and the researchers.

Collaboration with community partners such as school districts may lead to successful future CER. Forging a partnership between the National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded Science Education Partnership Award (SEPA) team at UNL and the Science Curriculum Specialist from one nearby school district, together we developed an event we named the “Science Connector,” in which all the district’s public-school science teachers came to the university campus for 3.5 hours of professional development. We invited university scientists from various fields to host tables describing their research and to talk with teachers one-on-one. Teachers met professional learning needs, and university scientists built relationships with teachers to demonstrate broader impacts of their research grants. We held the eighth Science Connector in 2021 with a new curriculum specialist, continuing our partnership with the district across staffing changes.

The goal of our newest SEPA project is to increase public understanding of network science. To help the K–12 science teachers understand the potential relevance of network science, we asked the curriculum specialist if we could survey teachers using a network survey (e.g., asking who teachers go to for advice) and present the results to them at the Science Connector. The curriculum specialist was eager to investigate the network structure of district teachers to assess the possibility of peer dissemination of teaching innovations. Thus, what started as a request to conduct a network survey of teachers for a presentation on the power of network science transformed into both a valuable tool to public school administrators and a longitudinal research study. The resulting research will advance fundamental knowledge of teacher advice networks over time and provide evidence about how those networks may have shifted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because we have an ongoing relationship with the school district and are responsive to the school district needs, we see this project as one of many ways that one study can enhance long-term collaborations in CER.

CER Can Be Messy, But It Is Meaningful

Sociologists conducting CER discover challenges, but these challenges often bring insights into the research. For example, even with shared goals related to solving a problem, partners might have different ideas about appropriate data and methods. Hill and colleagues (who are all applied sociologists and UNL Sociology graduate student alumni) engaged with community partners to evaluate an intervention in Indigenous communities. The intervention supported placing Indigenous youth who needed to be removed from their current homes into homes with Indigenous foster families. In many Indigenous communities, oral history and storytelling are culturally significant practices and provide more meaningful insights than quantitative data. Therefore, including focus groups of community members who care for Indigenous youth in foster care was important.

Building true partnerships involves listening, mutual exchanges, and working together over time. Pain and misunderstanding are part of the process; continuing to ask for clarification, recognizing power differences, apologizing, and seeking to do better are important for maintaining relationships. CER can require researchers to prioritize their relationship with community members over short-term research goals. Doing CER highlights elements of power (im)balance in research that can be hidden when long-term partnerships are not a high priority. A useful guide for working with American Indian and Native Americans, coauthored by a UNL Sociology alumna, provides examples of power abuses and ways in which communities have established parameters for appropriate research relationships. Several such parameters include explicit decision rules, inviting community members to contribute as coauthors, asking for feedback on and/or approval of drafts before sharing work publicly, and/or establishing publication agreements from the start.

Building long-term relationships takes time and energy. For students or early-career scholars, the timelines for earning a degree or tenure can make CER unfeasible. The close relationship with communities often means the data are dense and messy. Sometimes the specific social problems community members want to answer (e.g., will saving a grocery store help a small town?) do not easily map on to fundamental social science research questions that advance generalizable knowledge.

Despite some drawbacks, CER has benefits for researchers. They hear perspectives of community members and through collaboration generate insights that might not occur through more “one-way” approaches such as ethnography. Although ethnography suits some research goals, such as providing an “outsider’s” perspective on a community or studying a more ephemeral “community” (e.g., a protest movement), forging long-term researcher-community relationships through CER builds trust and the ability to respond quickly when opportunities to enrich the community and/or the research arise. Community partners may want expert help evaluating an intervention, and researchers may need to demonstrate broader impacts in grant applications. Ongoing collaboration with community stakeholders could serve as a place to pilot an intervention or a place to study the dissemination of the information. Overall, building and maintaining mutually beneficial (i.e., “win-win” relationships) is worth the time.

How Can Sociology Departments Support CER?

We described some of the history and foundations of CER at UNL in the introduction. Our department also supports undergraduate students through internships outside of the university, paid research opportunities with faculty (USTARS), opportunities to work in the BOSR, and a class called “Doing Sociology.” The department is explicit about training and support for academic and applied careers, funds a summer internship for a graduate student in the BOSR, advertises internships in applied settings, encourages graduate students to work with career coaches to create resumes, and connects current students with alumni in applied settings. Faculty also are rewarded in annual merit reviews for publishing with graduate students. In addition, UNL faculty grants that involved CER (e.g. NIH SEPA, NSF ADVANCE, and NIH COBRE) have provided graduate students paid opportunities to practice CER. For example, students have worked in a local public school research office to assess possible career paths and explore how to integrate CER with scholarship.

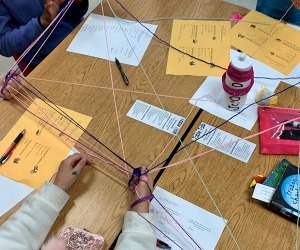

In an applied undergraduate “Doing Sociology” course led by Hill at Nebraska, students partnered with middle schools to conduct mutually beneficial research. In the fall the college students worked with youth in afterschool clubs, attended school meetings, and interviewed principals, teachers, and parents. In the spring the class surveyed youth with questions of shared interest to the undergraduates and community. The undergraduate students educated the department by reporting their findings in a poster session and the stakeholder community in a report and presentation for the . When considering courses like this one, sociologists should keep in mind the reality that evolving university budget models and strategic priorities can change the incentives for more engaged, labor-intensive courses.

As we have demonstrated throughout this article, CER creates multidimensional benefits. Sociologists working in academia who use theories to inform CER can advance basic sociological knowledge. CER enhances graduate educational programs and career placement since sociologists outside academia often conduct CER as part of their jobs. Nonprofit organizations, state, and local agencies have missions to serve communities that are relevant to sociological research. Often organizations need data to answer questions about how to best serve their groups or why specific interventions are more or less effective; trusted CER relationships can help them more quickly get needed information.

The National Science Foundation considers sociology a STEM discipline. Providing students with socially relevant CER experiences increases persistence in STEM fields, a crucial outcome for recruiting and retaining students from groups historically underrepresented in higher education. We argue that having sociologists everywhere—in as many settings as possible—improves specific communities and society. Moreover, encouraging more sociologists to conduct CER enriches sociology as a discipline and allows us to serve communities as they solve real-world problems.

Any opinions expressed in the articles in this publication are those of the author and not the American Sociological Association.